Last week, late-term abortion practitioner LeRoy Carhart killed a woman in a failed abortion at 33 weeks. The death of Jennifer Morbelli isn’t the first time Carhart killed a woman in a botched abortion.

Christin A. Gilbert, who was 19, died after a third-trimester abortion on January 13, 2005. After the botched abortion, Gilbert was rushed into the Wesley Medical Center ER in Wichita, Kansas. Gilbert suffered complications during her abortion that were not fully diagnosed, an autopsy concluded.

Cheryl Sullenger, of Operation Rescue, explained that Tiller sent Gilbert, who had Down Syndrome, to a local hotel after the abortion “even though her condition was worsening” following the botched abortion.

Cheryl Sullenger, of Operation Rescue, explained that Tiller sent Gilbert, who had Down Syndrome, to a local hotel after the abortion “even though her condition was worsening” following the botched abortion.

Eventually, the Kansas Board of Healing Arts claimed neither abortion clinic owner George Tiller nor his staff were responsible for the botched abortion death and refused to press charges.

In an extensive piece that follows, Sullenger provides the comprehensive story about Gilbert’s death at Carhart’s hands:

Christin Gilbert died from a botched third trimester abortion obtained at the now closed Women’s Health Care Services late-term abortion clinic in Wichita, Kansas. The following narrative is based on information gathered from the official autopsy report, 911 communications, members of Christen Gilbert’s family, first-hand accounts of eye-witnesses to the emergency transport, and information provided by a member of a 2006 Sedgwick County grand jury that investigated George Tiller’s part in the death of Christin Gilbert.

We remember her life and her heartbreaking death, with the hope that her tragedy might prevent others from experiencing her fate. Let her memory not be forgotten.

Click here for a list of women who have died from so-called “safe, legal” abortion.

Christin’s Life

Christin Alysabeth Gilbert was born on May 30, 1985 in Austin, Texas, but spent most of her life in the small Texas town of Keller. Christin had Down Syndrome, but that did not stop her from embracing life and living it to the fullest. Christin was raised by her family, which consisted of her mother, father, and sister.

Christin became involved in sports early in her life because it helped her meet people and make friends. She became very active in the Special Olympics and participated proudly for ten years. In 2003, she won the gold medal in the softball throw.

Christin graduated from the Special Education Program of Keller High School in 2004. While in high school, Christin became the inspirational member of the girl’s softball team, serving as their batgirl. Team members were never allowed to get down during a tough game because Christin would meet them at the dugout with hugs, telling them that she loved them. This kept spirits high and eventually her team won a state championship, an accomplishment of which Christin and her family were especially proud.

In life, Christin was a joy to be around. She happily made everyone who came near her the recipient of her many hugs. She was the center of attention when she walked into a room because of her outgoing and loving spirit.

Christin was loved by all who knew her and her death has left a void in the lives of her family and community. Christin was cremated and a private funeral service was held for her in her hometown of Keller, Texas, on January 21, 2005. In her obituary, Christin was called “one of God’s angels.” The 2005 Keller Special Olympics was dedicated to her memory.

What happened to Christin?

Tragically, sometime in 2004, Christin A. Gilbert was sexually assaulted in the State of Texas. As a result of the sexual assault, Christin became pregnant. A grand jury was convened in Tarrant County, Texas, to investigate Christin’s rape. However, no perpetrator was ever identified.

Christin’s mother only became suspicious of Christin’s pregnancy after noticing her enlarged abdomen while helping Christin bathe. She made an appointment for Christin with a local doctor, who confirmed that Christin was with child.

On Monday, January 10, 2005, Christin was brought by her family to Women’s Health Care Services, (WHCS), in Wichita, Kansas, for a third-trimester abortion at 28 weeks of pregnancy.

A confidential family source told Operation Rescue that Christin could not have legally consented to sexual activity because of the severity of her Down Syndrome condition, and that she never would have chosen abortion for her baby, leading to concerns that Christin was not made to understand what was about to happen. Christin was likely, according to the family member, a victim of an illegal forced abortion.

Neuhaus’ illegal relationship with Carhart and his employer, George Tiller

She was evaluated by a doctor who was purported to the family to be a “psychologist,” Dr. Ann Kristin Neuhaus, of Lawrence, Kansas. According to Kansas law, post-viability abortions may only take place when there is an agreement from a second doctor who is not legally or financially associated with the abortionist.

Christin’s abortionist was LeRoy Carhart of Bellevue, Nebraska, who was employed by George Tiller, MD, the owner and medical director of WHCS. At the time of Tiller’s death on May 31, 2009, he was facing disciplinary action by the Kansas State Board for Healing Arts – which could have resulted in the revocation of his medical license – on 11 counts of violating this provision of K.S.A. 65-670. The petition alleged that Tiller had a prohibited legal and financial relationship with Neuhaus, who exclusively provided the second signature for late-term abortions at WHCS from at least 2003, until January, 2007. This includes the time of Christin’s death. [Note: Solely due to his death, the Tiller petition has now been dismissed.]

Carhart begins the third-trimester abortion

After the possibly illegal Neuhaus evaluation, Christin was seen by Carhart an employee of WHCS, who gave her baby a fatal digoxin injection to the heart. Christin was prepared for labor and delivery of her dead child. Her cervix was filled with laminaria and she was sent back to her hotel room at the La Quinta Inn, located about 1-2 miles from WHCS on East Kellogg in Wichita. [Note: The La Quinta Inn terminated their arrangement to provide accommodations to Tiller’s patients and his staff in soon after Gilbert’s death. The hotel has been torn down and rebuilt at a different location.]

Christin did not eat dinner that evening.

The following morning, January 11, Christin was loaded into the family van where she expelled her dead baby on the way to the abortion clinic.

Christin arrived at WHCS where a D&C procedure was done on Christin and a “tear in the uterus” was sutured.

Fatal use of RU 486?

At this point, Carhart allegedly administered the abortion drug RU 486 to Christin. This drug is approved for medical abortions in pregnancies prior to the 6th week of gestation. The drug has been responsible for at least six deaths in the United States between 2001 and 2006.

RU 486 was apparently meant to be an “insurance policy” to make sure everything had been expelled from the uterus, but the drug was not approved by the FDA for that purpose. RU 486 was also approved as an oral medication, not as a vaginal suppository, which many believe contributed to life-threatening complications and deaths in women who used it in this way. It is believed that Carhart administered RU 486 to Christin as a vaginal suppository even though her uterus had suffered a laceration and was susceptible to infection.

Symptoms that Christin experienced after the administration of RU 486 were comparable to the symptoms of other women who have died from RU 486 nationwide, which include hemorrhage and sepsis.

Christin’s condition deteriorates

Christin was again sent back to her hotel, which doubled as both labor and recovery room for Tiller’s abortion business. This hotel was not equipped to handle the life-threatening complications that are known to result from dangerous third-trimester abortions. There, Christin’s condition began to worsen.

She returned once again to WHCS on Wednesday, January 12, and was diagnosed with “dehydration” although the sepsis was already spreading rapidly through her body. She was given intravenous fluids, but the clinic staff made no documentation of her treatment, or how much fluids were administered to her that day. That lack of documentation proved to be a prominent factor on the day Christin died.

Christin was again sent back to her hotel where her condition continued to deteriorate. Wednesday evening, the family went out for dinner, but Christin would not eat.

LeRoy Carhart is missing

Sometime that evening, Christin was cramping, bleeding, and vomiting, at times passing out. According to one physician who reviewed the autopsy report, aspiration of vomitus was the likely cause of her acute bronchopneumonia mentioned in the autopsy report.

By now, Christin was in serious trouble. Between midnight and 4 AM — there is a discrepancy in the testimony before the grand jury that investigated Tiller’s part in Christin’s death — the family called Tiller employee Cathy Reavis who was staying at the La Quinta Inn on call. Reavis was Tiller’s longest employee, having worked for him for 29 years at the time of Christin’s death. Reavis is identified as Tiller’s “patient coordinator” or “head nurse,” but she is not licensed in Kansas or any other state.

Christin was placed into a warm bath, which may have contributed to extra bleeding and infection. Reavis then helped get Christin cleaned up and back to bed.

Reavis called Carhart, who was supposedly also staying at the La Quinta Inn and was on call for emergencies. Carhart never responded and never saw Christin at the hotel. The whereabouts of Carhart during this time is unknown, as is the reason he did not respond to calls for help.

Final trip to WHCS

The next morning, Thursday, January 13, Christin’s family tried to get her ready to go to the clinic. Christin fainted and could not be revived. Instead of taking her to the hospital or dialing 911, Christin’s family loaded their bleeding, unconscious daughter on a luggage rack and wheeled her to the family van in which they returned her to WHCS at approximately 8:00 AM.

Once at the clinic, Christin awakened enough to walk through the door with assistance, but then collapsed. Her heartbeat and respiration stopped, or as the autopsy report stated, “she became unresponsive.”

Some efforts were supposedly made to revive Christin, but according to a grand jury source who inspected the medical records, for the next 40-45 minutes, there are no notations in the medical records about the care and treatment of Christin Gilbert.

Christin’s family was sequestered in a separate room and was unaware of what kind of treatment their daughter was receiving.

Possible perjury and a call to 911

Cathy Reavis testified before the 2006 grand jury that she had overslept on the morning of January 13, 2005, and was not at the WHCS until after Christin was taken away to the hospital. However, former Tiller employee Marguerite Reed told the grand jury that Reavis met her in the hallway of the clinic and instructed her to place the call to 911 that morning. Photographs taken by pro-lifer Judi Weldy clearly show Reavis’ vehicle in the clinic parking lot as the ambulance arrived and rounded the corner of the clinic.

At 8:48 AM on Thursday, January 13, a 911 call was placed by Reed, who pleaded with the 911 dispatcher, “Please, please, please! No lights, no sirens!” She was evasive with the dispatcher and placed him on hold for 45 critical seconds while she inquired of Reavis about how much she should tell him. Reavis told Reed that she couldn’t tell her why, but that she just needed to get the ambulance. Reed clearly downplayed the true nature of Christin’s rapidly deteriorating condition. Sensing no urgency, emergency responders arrived on the scene at 8:57 AM, a full nine minutes after the call was placed.

Paramedics arrive

When paramedics arrived, they saw Christin lying in what was described as “huge amounts” of “coffee grounds” blood and fluid — “way more than you would normally see.”

LeRoy Carhart was on top of her trying to physically force fluids from her stomach. Paramedics indicated that they first thought he was a male nurse who may not have known what he was doing. The paramedics ordered Carhart away from the girl but he did not comply. A male paramedic was forced to “very sternly” demand that Carhart step away from the girl. One report indicated that the paramedics may have actually pulled Carhart off her.

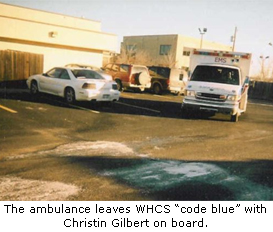

The ambulance crew spent 15 minutes treating Christin’s dire condition, which included cessation of respiration and cardiac arrest, from which she was resuscitated. At 9:14 AM, Christin was transported via ambulance with all haste to Wesley Medical Center’s Emergency Room, and arrived at 9:18 AM after a four minute ambulance ride. Pro-lifers photographed the ambulance at WHCS and George Tiller’s arrival at the ER.

At Wesley Medical Center

Once at Wesley Medical Center, the autopsy report showed evidence that Christin was bleeding from the mouth, vagina, eyes, and every other orifice. The emergency team who treated Christin worked aggressively to save her life, but it was too late. The family was advised of her condition, and reacted by telling the doctors to harvest her organs for donation. Huge amounts of antibiotics were pumped into her failing body, but to no avail. Because the sepsis was not treated in time, Gilbert suffered from systemic organ failure. All the blood vessels in her reproductive organs were clotted.

Christin was given pain medication, but little else could be done. She was pronounced dead at 4:14 PM, January 13, 2005.

Christin’s eyes were donated but the rest of her organs showed signs of hemorrhage and were not suitable for donation.

Christin’s unclothed body, with medical implements that had been used in an attempt to save her life still attached, was sent to the Sedgwick County Regional Science Center on January 14 for autopsy. Seven months and ten days later, the report was released to the public with evidence of her botched abortion.

Operation Rescue goes public and seeks answers

Operation Rescue broke the story when it dropped a press release on January 13, 2005, announcing the documentation of an emergency transport from WHCS. Efforts to conceal Christin’s death were already underway. A KNSS reporter was expelled from the WHCS property after seeking answers about the incident.

On January 19, 2005, while conducting a first amendment activity outside Wesley Medical Center, Troy Newman was contacted by a member of law enforcement who told him, under the condition of anonymity, that the abortion patient that we had seen transported to Wesley on January 13, had in fact died.

Conversation with Vicki Buening

CLICK LIKE IF YOU’RE PRO-LIFE!

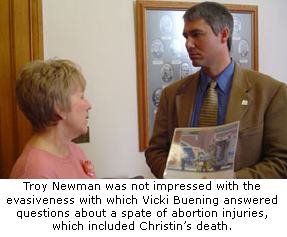

On January 21, 2005, Troy Newman and other members of Operation Rescue visited the office of the governor and spoke with Vicki Buening, the governor’s Director of Constituent Services. When showed a number of photos of several ambulance runs from WHCS to the local hospital, Mrs. Buening told Newman that if women were unhappy with the care they received at WHCS, they were free to file a complaint with the Kansas State Board of Healing Arts. Mrs. Buening was the wife of Larry Buening, who at that time was the Executive Director of the Kansas State Board of Healing Arts.

The following is an exchange between a visibly nervous Vicki Buening and Operation Rescue’s Senior Policy Advisor, Cheryl Sullenger, which took place during that meeting:

Buening: “Now individuals involved in any of these kinds of mishandling of their medical care have the option to file a complaint against their provider with the Board of Healing Arts.”

Sullenger: “If they’re still alive.”

Buening: “Certainly that is true. Whether, uh– [pause] — Yeah, you’re right. But I, uh…”

Sullenger: “If they are dead, they can’t file a complaint, can they?”

Buening: “I don’t have an answer to that question.”

The impression gathered from that conversation by Sullenger was that Buening was aware of Christin’s death, but was hiding it.

Operation Rescue issued a press release on January 25, 2005, announcing that it had confirmed that Christin and in fact died from her botched abortion.

KSBHA complaint filed

Sullenger filed a complaint with the Kansas State Board of Healing Arts against George Tiller in the death of Christin Gilbert, since Christin obviously could not file on her own behalf. Sullenger received a letter dated January 26, 2005, from Shelly Wakeman, KSBHA Disciplinary Counsel, advising her that an investigation had been opened based on Sullenger’s complaint.

Sebelius intervenes for political reasons

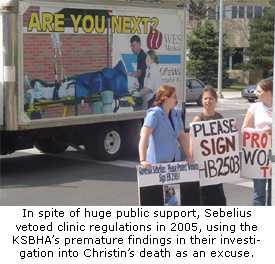

Meanwhile, a bill was introduced in the Kansas House of Representatives, HB 2503, which would have placed regulations on clinics that do abortion. The bill was strongly opposed by then Gov. Kathleen Sebelius and Tiller’s now-defunct Political Action Committee, ProKanDo.

Sebelius received large campaign contributions from Tiller and ProKanDo during her 2002 campaign for governor.

On February 2, Sebelius sent a letter to Larry Buening asking him to look into the death at WHCS.

March 15, 2005, Operation Rescue held a press conference in the Capitol rotunda supporting HB 2503. A former Tiller patient told of her horrific experience at WHCS a number of years ago and of her inability to bear children since suffering abortion injuries. Sullenger discussed the death of Christin Gilbert. A legislator who was present at the press conference believed the statements would be beneficial to the bill and asked them to testify before an upcoming committee hearing.

On March 22, 2005, Sullenger and Cramer testified before the Senate Public Health and Welfare Committee in support of HB 2503, even though Cramer had been contacted by ProKanDo Director Julie Burkhart in what Cramer viewed as an effort to intimidate her to keep her from testifying.

On March 23, 2005, Operation Rescue issued an e-mail containing the former Tiller patient’s story along with Sullenger’s testimony that was distributed throughout the United States, urging supporters to voice support for HB 2503.

On March 25, 2005, Larry Buening issued a letter (pg. 1, 2) to Gov. Sebelius with an “interim” report on the Gilbert death indicating that their preliminary determination was that Christin had received care that “met the standard of accepted medical practices,” even though the autopsy report had not been released and a cause of death had not been determined.

Buening noted in that letter, “The Board is aware that office-based procedures and clinic licensure are currently being considered by the Legislature and wanted to provide you with an interim report.”

This statement gives cause to believe that the Buening letter was politically timed and motivated, and that his determination was such as to please the governor.

But Buening’s efforts to minimize Christin’s death before the legislature were partly unsuccessful. Later that day, the Senate passed HB 2503 with an unexpected two-thirds majority, due in part to the pro-life testimony, and lobbying efforts made by Operation Rescue highlighting Christin’s death.

Sebelius later vetoed the bill, basing her decision in part on the premature conclusions drawn by Buening in his hastily written letter of March 25, 2005. An attempt to override failed.

Autopsy report released

On August 24, 2005, the autopsy report on Christin’s death was finally filed, indicating that she “died as a result of complications of a therapeutic abortion.” The report made no mention of the names of physicians who treated Christin, nor did it mention the name of the abortion clinic. Other autopsy reports filed by the Sedgwick County Coroner routinely included such information.

KSBHA quietly sweep Christin’s death under the rug

On the afternoon of November 23, 2005, the day before Thanksgiving, the KSBHA released its final determination that absolved Tiller and his staff of wrongdoing and closing the case both in a detailed letter to Sebelius [pg. 1,2,3] and in a terser, less informative response to Sullenger who filed the original complaint.

After dismissing the complaint, KSBHA Director Larry Buening was questioned as to why the official autopsy report findings were essentially ignored by the Board. Buening told reporters that the autopsy report released by the Sedgwick County Forensic Science Center was merely one “opinion.”

Pro-life groups suspected a cover-up involving Sebelius, who had received a great deal of campaign support from Tiller.

Citizen-called grand jury

Unsatisfied with the Board’s decision, and believing strongly that the determination was politically motivated, Operation Rescue and Kansans for Life launched a citizen’s petition to call a grand jury to investigate Tiller in the death of Christin Gilbert.

On April 19, 2006, the grand jury petitions were certified and on May 22, 2006, the grand jury convened and began its investigation.

But on July 31, 2006, District Attorney Nola Foulston announced that the grand jury had dismissed without issuing an indictment.

Grand jury foreman comes forward with new information

However, the man who served as foreman on the grand jury contacted Troy Newman shortly after the grand jury dismissed and offered an interview. Newman and Sullenger met the grand jury member and recorded the interview. Based on his information, Operation Rescue published via the Internet a four-part series called “Justice Aborted,” which detailed information uncovered by the grand jury investigation, and revealed the fact that the grand jury failed to indict Tiller on four counts by only one vote. That series was published between August 10 and 17, 2006.

In that interview it was learned that the grand jury had attempted to subpoena LeRoy Carhart, but was unable to because Carhart dodged the subpoena, and Asst. District Attorney Ann Swegle, who was assisting the grand jury, would not issue the subpoena in Nebraska, where Carhart lived.

The grand jury also tried to get a copy of Neuhaus’ record to see why she thought that Christin’s third-trimester abortion was legally justified. Swegle told the grand jury foreman that it would take an “act of God” to get that record. She made no further efforts to obtain the record, which impeded the grand jury’s ability to make an informed decision about the legality of Christin’s abortion.

KSBHA Arrogance

Two representatives from the Kansas State Board of Healing Arts (KSBHA) appeared before the grand jury. One was attorney Mark Stafford and the other was an unidentified woman. Their testimony did little to answer questions about the care Christin received, especially during the 45 minutes she was at the clinic on the day she died.

“These people all had attitudes,” said a confidential source inside the grand jury process that spoke with Operation Rescue. “The people involved from the Healing Arts, those people were arrogant, ‘We’re better than you.’ Their attitude was, ‘We can do no wrong.’”

Standard Protocol?

The KSBHA representatives did not reveal details of their investigation to the grand jury. It seemed that they expected the grand jury to simply accept their findings, without question.

“‘You know what this is, just normal protocol,’ were the words they all kept using,” said the source.

“‘This is standard protocol, and we had our own investigator, and he found no fault in what was going on.’ It was just the whole attitude from all these people that are in — in my opinion — a small fraternity.”

But details that have surfaced indicate that Christin’s third-trimester abortion was anything but “standard protocol.” Irregular treatment included a gross misuse of RU 486, which is approved only for use in early abortions under six weeks gestation. Abortionist LeRoy Carhart instead used the dangerous drug, which is responsible for at least 6 U.S. deaths since 2001, as an “insurance policy” to make sure the contents of the uterus were expelled in case Carhart left something behind after the D&C.

“If a doctor cannot competently perform a D&C, he is incompetent to practice medicine,” said Operation Rescue’s Troy Newman. “There is just no gray area here or any question. Carhart’s misuse of RU 486 put Christin’s life at risk and may have killed her. That is not ‘standard protocol’ in anyone’s book.”

Also irregular was the lack of notation as to the amount of fluids Christin received for dehydration on the second and third days of her abortion, and the lack of documentation of the treatment Christin received during the 45 minutes she was at Tiller’s clinic on the day she died.

“Is it standard protocol to pump someone’s stomach when she hasn’t been breathing or had a heartbeat for 40 minutes? Is it standard protocol not to call 911 for 40 minutes after someone has gone into cardiac and respiratory arrest? Is it standard protocol to omit from a patient’s chart the care received, especially during a fatal incident?” asked Newman. “These questions were not answered by the KSBHA or any other witness.”

The grand jury source indicated that the jurors were given the run-around by KSBHA witnesses. “‘No, no, no, we had our own investigator, Mr. So-and-so, da,-da, da-da, da-da.’ And that’s really how this thing went,” said the source. The KSBHA representatives expected the grand jury not to question their findings, and addressed questioning with condescension.

“The thing was just — from the Healing Arts people we interviewed — it’s like there is no ‘wrong.’ But yet, there’s someone dead over this,” said the source.

“Three and Out”

The grand jury was told that the KSBHA has a “three and out” policy, meaning if a doctor appears before the Board three times and is convicted, he loses his license.

It was asked how many times Tiller had appeared before the Board. The response was seven times.

“We asked, ‘Well, what happened to your ‘three and out’ policy?’ ‘Well…’ and they go into their little justification of Tiller,” the source said.

When the source was asked if he believed that the KSBHA was covering for Tiller, the source said, “That’s right! That’s exactly what it is.”

New investigation requested

Based on the new information that surfaced after the KSBHA closed the complaint against Tiller, Operation Rescue became convinced that LeRoy Carhart was primarily responsible for Christin’s death and that Tiller was only minimally involved in Christin’s abortion, yet bore some responsibility as Carhart’s employer and as the owner and medical director of WHCS.

In April, 2008, the Executive Director of the Kansas State Board of Healing Arts Larry Buening resigned under pressure and amid scandal for failure to discipline physicians. Buening was a personal friend of George Tiller, and was allegedly responsible for allowing the improper Neuhaus relationship to be overlooked by the Board. The next day, General Counsel Mark Stafford also resigned. Stafford had repeatedly stonewalled pro-life groups as they sought answers and demanded action in Christin’s death.

These resignations led to a wholesale purging of the KSBHA that took place over the course of several months.

Former Tiller and Sebelius cronies were replaced with an executive staff that did not have the connections to the abortion lobby.

Operation Rescue believed that the investigation into Christin’s death under Buening was politically timed and its determinations politically motivated, casting suspicions on the Board’s determination to close the case. After the Buening/Stafford resignations and other personnel changes, the Board appeared to have been purged of corruption. Because of this, Operation Rescue filed a complaint in February, 2009, asking that the inquiry into Christin’s death be reopened, this time focusing on Carhart’s role in her abortion. However, the KSBHA later notified OR that it would not reopen the case.

WHCS permanently closes

Then on March 31, 2009, Tiller was murdered in Wichita, Kansas, an act of violence strongly denounced by Operation Rescue. The Tiller family made the decision to permanently shutter WHCS, an action that closed a chapter in the nation’s debate over late-term abortions and liberated Kansas from the reputation as the Abortion Capital of the World.

LeRoy Carhart then promised to begin providing late-term abortions at his abortion clinic in Bellevue, Nebraska, while he continued some attempt at reopening a late-term abortion mill somewhere in Kansas.

As of this writing, however, neither of Carhart’s plans have come to fruition. Currently, there remains no one in Kansas that will provide post-viability abortions.

Christin Gilbert’s death was a catalyst that helped open the eyes of the people of Kansas, including the Legislature, to the horrors of late-term abortions. If her story can warn others and spare even one life, then her death was not in vain.

LifeNews.com Note: Portions of this article written by Cheryl Sullenger. Cheryl is a leader of Operation Rescue, a pro-life that monitors abortion practitioners and exposes their illegal and unethical practices.